Who buys facts?

The conflict over which statements are perceived as fact and which are not is a proxy for some other conflict relating to power. It may be that because communities define their borders based on adherence to what is knowledge and what is not, that communal conflict is rooted on who has the liberty to believe what they want to, and who has authority to define membership based on adherence. It may be that in some societies, a leader is able to look you in the eye and lie to you, and they know you know that they are lying, but it is such an expression of power that you can’t call them on it. And that re-affirms their power. Maybe that’s the point?

In anticipation of the question: “Who’s to say what’s a fact and what isn’t?”, please refer to this previous post. A fact is a statement rooted in ground truth. It compiles as true.

As a product of a WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) society, I like facts. I consume a lot of them. They help me make up my mind. Factual information is an essential ingredient to a free, competitive, and viable society.

Facts cost money to make. Facts cost considerably more than lies, fiction, fibs, fantasy, fraud, and delusion. A lot of people have difficulty in discerning what is a fact and what is a lie. And sometimes, the shared delusion of what is a fact, what might be a fact, what is likely not a fact, and what is probably a lie, is unto itself the good.

When I was growing up, grocery stores used to place bundles of paper next to the checkout counter where people might buy them out of impulse, while they’re waiting for the cashier to scan all your groceries. These publishers understood the decision window. They needed to get you to pick them up, scan, and toss them on conveyer belt. Some of them would run stories about celebrities. There used to be a lot of stories about Princess Diana and Michael Jackson. Some of it gossip. Some of it deliberately planted by publicity agents. If the public was chattering about you, then you were bankable. That kind of interest could be transported into foldin’ money.

Gossip and celebrity photographs were still relatively more expensive than pure fiction. Informants and paparazzi alike needed cash. The most bankable celebrities didn’t harass themselves. So, naturally, there had to be a niche for something a bit more fictional. And did they deliver!

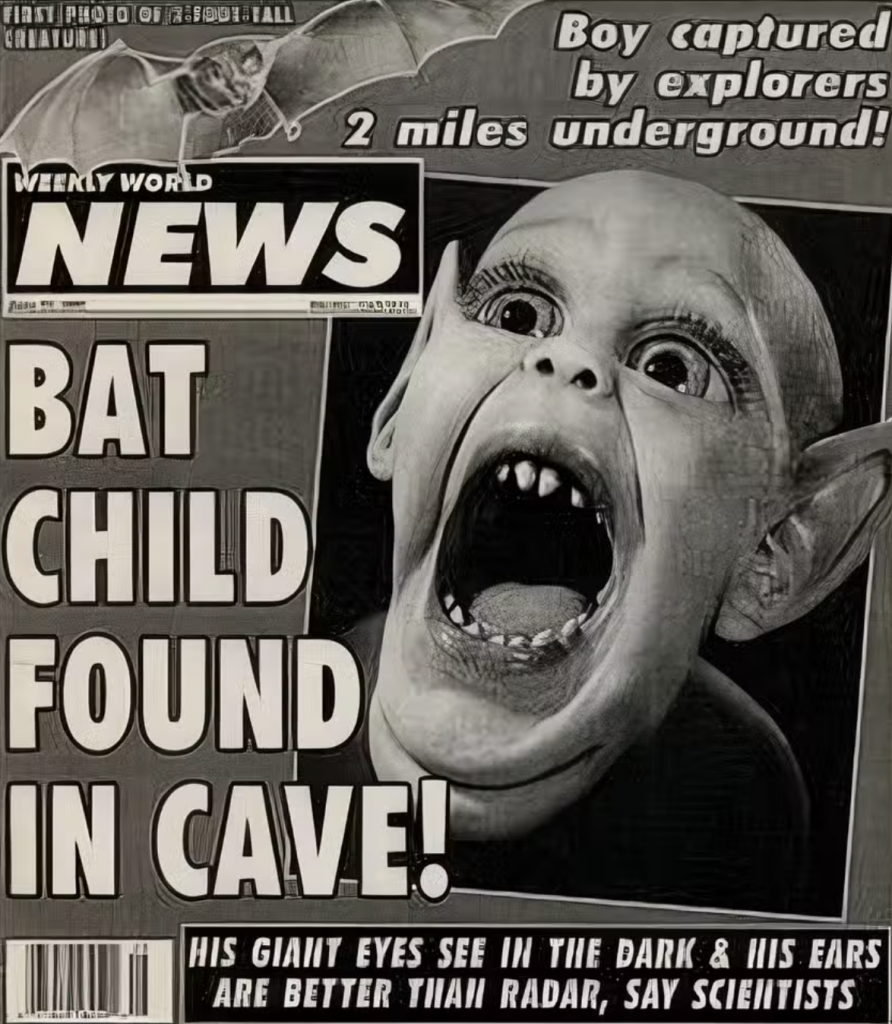

One title was called: Weekly World News.

It would carry fantastical stories about a bat boy found in a cave and Elvis still being alive.

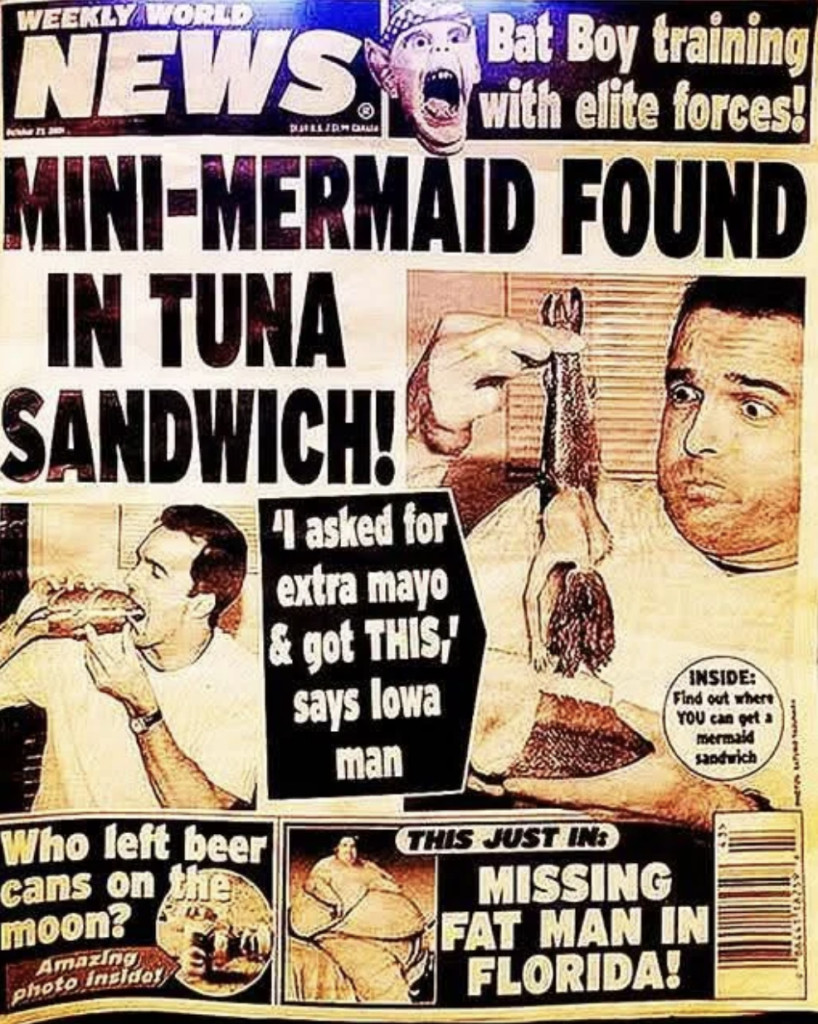

The “Mini-Mermaid found in Tuna Sandwich” headline even came with the saucy promise of finding out where YOU can get a mermaid sandwich.

This was entertainment. They called it news, and their commitment to the bit made it all the more funny. To quote Dame Edna after the public feud with Selma Hayek : “If you have to explain satire — don’t.”

The world changed and even the venerable Weekly World News couldn’t economically continue to print their form of entertainment. Demand changed.

What I didn’t know growing up was that some of those magazines were buying stories from people are then soliciting offers from celebrities to keep those stories in a safety deposit box. So, on the one hand, the publisher had a vehicle to affect public opinion about celebrities at the checkout counter, alongside publications that most people understood were fictional entertainment, and then you had publications that were in this grayish zone of gossip. You don’t quite know what is a fact and what somebody is getting paid to be true, what is publicity, and what might be all three at the same time. And then there often magazines that were glued (not stapled) together that featured approved publicity pieces and would declare various men to be the sexiest alive. But hey, you’re talking about it, aren’t you?

Email disrupted some of this content, and the newsfeed followed around 3 years later for most people in WEIRD countries.

So, let’s say that going all the way back, in the Anglosphere, to The London Intelligencer, there’s always been a market for a mix of fact and fantasy, there’s a spectrum with it, that might be like a sandwich. A lie, perhaps like a mermaid, is best concealed between two slices of truth.

At the far end of this spectrum are facts. Unironic, hard, cold, enough-eyes-on-the-claim, fact.

Some financial news is like this where anchors will dryly state what West Texas Intermediate closed at as they run the stock fotage of oil pumped into barrels on a conveyor belt and the sun rising behind oil rigs. The closing prices of different indices, securities, and currencies are quoted. Verbatim from earnings calls. “So and so said: _____.” is typically a statement of fact. They said that. Regardless of the factuality of what resides within that blank, there’s typically a transcript you can go and look at or a recording you can hear for yourself.

Weather can be like that too. In some parts of Canada the weather forecasts are extremely technical – they’ll have a real scientist with media training point to the isobars on the map and warn you how windy it’s going to be. And in other (urban) markets they’re much more worried about getting blamed for a single drop of rain on a picnic this Saturday afternoon so they’ll inflate the POP estimate Environment Canada is reporting to cover themselves.

Certain types of journalism makes an effort to report facts. Politicians will go to the sticks and say all kinds of things, and that video may be replayed so you can hear them say the things they said. Again, the factuality of what they are claiming is often suspect. Sometimes a journalist will open a document that a public official has created and quote from that. They’ll pull a quote from an auditor general’s report or the Transportation Safety Board. Sometimes they’ll do a streeter, talk to some man or woman at random so that hopefully they say a single sentence that can be sliced into a package. “It’s hot out here!” and “groceries are too expensive” and “all fines are cashgrabs!” are three such refrains you’ll hear. Valuable input from the pubic. Vital. Vital stuff.

People buy what’s relevant to them. Some people can’t act on facts, so they have no use for them. This might be subtle. If I’m going to be talking to anybody from Calgary, I look up the price of a barrel of WTI, so as to give the customary Calgary greeting. If I’m going to be talking to somebody from PR, I’ll load up TMZ so I can give the customary PR greeting. If I’m going to be talking to a farmer, I’ll look up the snowpack numbers so they can grumble at me about soil moisture come spring.

I’m curious about how the world works and want to understand it. I find that entertaining. I don’t know what difference it makes. I’m not in any more position than you are to rectify the absolute catastrophe of living on this planet.

There are some facts that are more useful to have before others have them.

Those who need facts the most

Those with power.

And that’s a lot of people!

WEIRD countries emphasize collective leadership and collective power. It’s pretty slow but unreasonably effective once decisions are made. When there’s a lot of misinformation in the consensus generation system, it takes the community a lot longer to sort out what is fact and what is fiction. Everybody, in a democracy, exercises fractional power. Those who are elected have a fair bit more of it, but there’s a keyword there in terms of representative. People tend to be representative of their constituents and the great ones actively consider which policy outcomes would be beneficial to them! In other words, they best ones serve the interests of their constituents and their societies. So if the constituency is bathed in fiction, it follows that it’ll be that much more difficult for a representative to come to consensus with everybody else. And every democratic system contains checks upon checks upon checks – some obvious, many hidden.

Facts cost money. And there aren’t as many people making them anymore. 1000 US counties don’t have a journalist. That’s wild. That’s systems destroying. That’s wealth destroying. That’s ultimately society destroying.

How of much of this is driven by a disruption in business models, and how much by something else?

It’s as though the conflict over which statements are perceived as fact and which are not is a proxy for some other conflict relating to power.

If you have power, you need facts.

What do you think?