What is the planning fallacy?

The planning fallacy is the tendency of people to underestimate how long they’ll take to complete a task or project.

Why are we struggle at estimation?

Kahneman and Tversky (1979) thought that it had to do with information input. When people estimate, they tend to consider only factors related to the project that’s in front of them, instead of considering factors from prior experience. The approach of only thinking ahead doesn’t have the benefit of considering more factors and considerations. It may also feel a lot better to think ahead than to recall the painful trauma of failed projects of the past. And yet, the past can be a fantastic source of factors.

I’ve had software projects get delayed by strikes, floods, hurricanes, client collapse, fraud on the client side, injury, unpredictable illness (aside from the predictable September illness wave!), death, global pandemic, shakeups in executive structure, priority shifts, resignations, mass layoffs, technical debt that was represented as much lower than it really was, changing tastes, SQUIRREL!, legitimate changes in fundamental system specifications, API changes, poor documentation, missing documentation, technical disruption, maliciously altered documentation(!) and both female and male pregnancy. Just to name a few!

What Justin Kruger and Matt Evans (2004) added to the conversation was the idea that in addition to thinking of the past, one could be a lot more deliberate about thinking of the future, too! What if a person was induced to think carefully about how they were going to accomplish a task, step by step? They suggested that to get a very good estimate, that you needed to unpack all the tasks required to achieve a goal.

Unpacking is just what it sounds like. Take a large task, like preparing a meal or doing your holiday shopping, unpack it into steps, and then estimate the steps. Add up the estimates to reveal the final estimate.

And it worked in the lab. Participants who were prompted to think about all the steps involved in accomplishing a task made more accurate estimates.

So that’s the planning fallacy and those are the steps to avoid bad estimates from happening to you. Unpack!

But wait, there’s more!

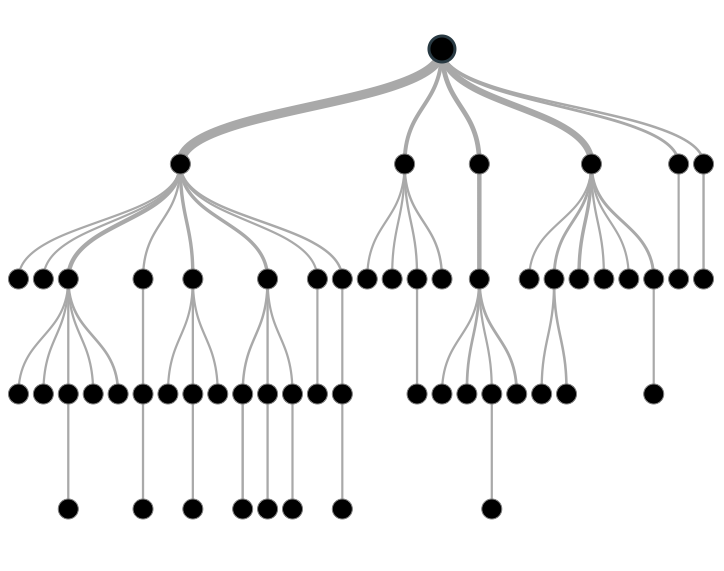

I don’t know about you, but I love a big, tall, decision tree, with lots of leaves down at the bottom. There’s nothing quite like a stroll through a random forest too. The leaves are absolutely gorgeous in the autumn!

It’s almost always to make planning a community event. Diverse groups of people are great for this. They contribute so much more diversity of leaves to create these incredible, lush, beautiful trees. And nice, big, fluffy trees tend to generate such better outcomes because decision makers have more futures to choose from. They have more branches. This is well worth the effort, especially in important, strategic, contexts.

Thinking of the past helps you to discover of more branches and leaves in that decision tree. Challenging yourself to think of the factors that were outside of your locus of control, and the factors that were within it, helps you identify branches you can influence, branches that may come at you, and, most importantly to my friends in data science and product management, inform what data you need to collect in advance of the branch.

Decisions trees can help you think about the future. They help you chunk the future in a way that is empowering. Instead of confronting a kind of sad fiction that the future is linear and gray, one can engage, meaningfully, in the co-creation of a great future. It lays bear all the choices you can make to realize a better future.

Planning is the preparation of the mind.

These tools can help.

[1] Kruger, Justin., Evans, Matt (2004) “If you don’t want to be late, enumerate: Unpacking reduces the planning fallacy”, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. (40) pp. 586-598.