The Quality Attributes of Virtual Information Goods

A quality attribute, in systems engineering, is a non-functional requirement. You can think of it as an adjective that describe a system.

Consider information virtual goods and the different kinds of deals we’re presented with [1].

One major design pattern is that a group of people gather information, concentrate it into a single artifact, and distribute it. You pay attention to that artifact. In exchange, a portion of your attention is sold to yet another group of people who are willing to pay for that attention. Those artifacts in the 20th century included: the newspaper, the magazine, the radio broadcast, the news reel, the 30 minute, 60 minute, and 24 hour linear television newscast format. Towards the end of the 20th century the artifacts expanded to include: the webpage, the web video, livestream, and the audio podcast.

From the perspective of the people gathering information and concentrating it into a single artifact, a part of what they are doing is gathering the attention of an audience and concentrating it, so that they can sell it to a third party. Sometimes the act of concentrating information and concentrating audiences seem to be the same. Sometimes content creators are quite emphatic that they are not business people. For much of the 20th and 21st century, the deal was that the creatives would create the content, and the advertisers would create the advertising, and the linear content, along with your attention, would be split between them.

For instance, imagine that it is 1990 and that you want to concentrate information about skateboarding. You might select the medium of a magazine. You would gather information about skaters and information relevant to skaters, and distribute that magazine to retailers where skaters are likely to buy it. Maybe you imitate The Economist magazine and throw in a dozen subscription cards in there so they come out and spread like neoliberal confetti. It totally doesn’t irritate anybody, and it guarantees building a direct to subscriber base. In addition to the subscription revenue and retail sales, you would sell space inside the magazine to people who wanted to communicate to skateboarders. The distinction between content that is attractive to an audience, the audience itself, and the people who want their attention might not have been nearly as evident at the time. But, that’s how it worked. These distinctions matter when thinking about the nature of information virtual goods.

The information that is transmitted in those mediums is a virtual good. I’ve oversimplified the situation to be understood. Different groups of people have sharply different beliefs about what they’re doing when they’re creating or aggregating content, audiences, or advertising.

There are several quality attributes of information itself.

The four I’ll focus on are:

- Is it relevant?

- Is it timely?

- Is it intelligible?

- Is the information true?

The world creates data every single second of the day. To the vast majority of people, the vast majority of that data is not relevant. The overnight temperature in Birao is just as relevant to a snow plow driver in Carrot River as the price of diesel in Carrot River is to a farmer in Birao. Not much relevance there. And from the grand perspective every bit of information and every second of attention fuelled by the calories in your brain: The world is awash in irrelevance.

Many have benefited from the ability to gather, organize, and distribute information into relevant packages that find relevant audiences. The ability to predict how different types of information might appeal to different types of audiences can be a profitable one. The first newspapers in London contained information gathered and organized in London, sent off to Belgium to be printed, and shipped back to London to be distributed. It had the information that an audience of the time wanted to read about – mostly gossip about what those in power were up to. Allegedly there’s some good information about the English civil war. It’s kind of neat to think about the literacy rate as a key factor limiting total addressable market at the time.

Today, there are entire operations dedicated to gathering, organizing, and distributing the information they figure people want to know, and, what they don’t want to know. Google built an entire business around predicting what is relevant to you based on the words you used to find information, problems, or solutions.

Relevance can be contested. Some outlets organize information in order to tell you things you don’t want to know, in order to make you feel angry and informed. You might not find it relevant to your life at the time, but often a story about alleged corruption, if left unchecked, can add up in a massive problem in your life. If those in power are status-minded, then shame may be used as a powerful accountability mechanism.

The assessment of relevance is in part a function of the preferences of an individual, and, in part, a function of the preferences of the person creating or aggregating the information. Sometimes a single piece of information isn’t all that relevant on its own, but it may become so if a social relation believes it to be true, or because a linear broadcast is devoting thirty minutes to it. There is a virtual concept of habit-trust-loyalty that is believed to exist. There’s even a belief that by virtue of making something prominent, it is supposed to cause it to be relevant.

Timeliness is closely related to relevance. Warning of an earthquake before it arrives is useful. Warning of an earthquake ten minutes later isn’t as useful. Certain artifacts dealing with history can be very useful if they’re framed. Some people compete with each other to be the first to tell you something they think is relevant – to get that big scoop – to proclaim BREAKING NEWS over and over again throughout the day to drive a sense of importance and urgency in order to capture your attention and keep the advertisers paying.

On Intelligibility – either somebody can read and understand information or they can’t. Some communities define themselves by knowledge contained in the words they understand. They use language to make distinctions. Some information goods, in order to be mass, have to be lowest common denominator. They have to be intelligible by everybody who can understand a couple thousand words. A lot can be communicated simply: what will the weather be like tomorrow, did the local sports team win the big game, and here is a scapegoat to blame for everything because the real cause is complex — rabble rabble rabble. Rage and love are the universal languages. Satire is unintelligible to a portion of the population, and as such, is confusing at best or is believed at absolute worst. Scientific communities develop language to communicate amongst themselves, not to exclude the public, but to advance the conversation they’re having amongst themselves. Most academic journals are entirely about experts convincing other experts as to what is knowledge and what is not. The good stuff is often simplified for the lowest common denominator in such a way that it is not accurate. The relationship between intelligibility, simplicity, brevity, and reality is complex. The tradeoffs are brutal.

Then there is truth.

Truth seems to be a very difficult concept because it’s fraught with paradox. I was struck, earlier this month, by an exchange between Judge Maya Guerra Gamble and Alex Jones. Judge Guerra Gamble told Alex Jones that, “Your beliefs do not make something true,” and “Just because claim to believe something is true does not make it true.” (August, 2022)

I wonder how different people might parse those words and understand them differently.

The human imagination is wild. There are audiences for information that is not true. At one time these virtual goods fell into a category that was widely acknowledged as fiction. Some people find it fun to think about the Egyptian Pyramids and their origin as alien artifacts. It isn’t true, but it’s kind of fun to think about. Satire enables one to create entire alternate Universes that are not true. The creators of those virtual goods have a pretty good grasp on what an audience wants to experience, and a distributor, incredibly, The History Channel, can bring those pieces together. Mister Rogers taught many North American children that it was okay to Make-Believe. Science Fiction and Fantasy continues to create entire worlds of what-if and wonder and often dominates both popular and unpopular culture. Those who follow this space know how much I enjoy biting satire. Satire is an acquired taste. Why would people make up things that aren’t true and call it satire? Because the creator is saying something about reality that is surprising (divergent) and relevant. It’s great. Information doesn’t necessarily have to have the quality attribute of truth for it to be useful.

It’s easy to understand why good people can be confused.

There are audiences that appear, on the face of it, to value the quality attribute of mistruth in contexts beyond entertainment and Make-Believe. For them, it might not be so much about the entertainment, the infotainment itself, but the secondary effects of that entertainment. If it is inevitable that a niche for a given virtual information good to exist, then it is inevitable for somebody to attempt to fill that niche. In the United States and Canada, the state is typically reactive and very slow, which enables all kinds of interesting and weird things to happen.

Consider the Canadian linear local newscast. Often, the people who report the news also engage in advertising. It began, at first, with the meteorologist working ads into their forecasts. Then it spread to their consumer reporter, as it’s much easier to say a few lines about which speakers to buy and paste together some b roll of people listening to music, to ask if a mattress mat is the right solution for you, or which crooked kitchen renovation contractor you should avoid, than it is to do serious reporting on consumer fraud. It keeps the advertisers happy. It keeps the business of the editor’s back. Then it spread to the anchors themselves. Often, the same people that told you about a crooked politician in the opening three minutes of the newscast are telling you about which holiday destinations to consider in the last three. Then it got worse. Hard news anchors began showing up in fiction like House of Cards (US). The lines between what is journalism and what is not became extraordinarily blurred.

It’s against this already blurry media landscape that a new market appeared and grew.

There is a market, an audience, that demanded stories denying that the massacre at Sandy Hook ever happened.

Isn’t that interesting? It is relatively easy to understand how information about skateboarding is packaged and distributed for people who find information about skateboarding to be relevant, timely, intelligible, and true. But what of the market that demands information about Sandy Hook that is relevant, timely, intelligible and … untrue? Who did they trust to tell them that story?

What of the link between truth and trust?

According to Edelman’s Trust Barometer, trust is low:

“Around two thirds of Canadians believe journalists and reporters (61%) and business leaders (60%) are purposely trying to mislead them, with government not far behind (58%). Further, less than half of Canadians view government leaders and CEOs as trustworthy (government leaders at 43% and CEOs at 36%).”

(It’s similar in the US – “Failure of leadership makes distrust the default.”)

The sense that people are being lied to by journalists and reporters are trying to mislead them is a mainstream belief. And that belief in lying is linked to policy failures. They’re lying to you because they’re covering up their failures. It’s in this kind of environment that it’s possible to imagine an audience for stories that are contrary to what the mainstream is reporting. If one believes that the establishment is, at best, screwing it up, and at worst, deliberately hurting them, then one could imagine a market for information that is either independent or in opposition to what they perceive is the establishment.

It’s conceivable that even if much of the audience does not truly believe that events at Sandy Hook was a conspiracy, the appeal of the story is a way to fight back against a failed establishment. The repetition and amplification of the story as a way to reciprocate the way they perceive they are being mistreated.

An eye for an eye. A lie for a lie.

I might go so far as to assert that policy failure causes to distrust. The distrust leads to the co-creation of both an audience and content that reflects their interests. To be most generous it is about the seeking of alternate perspectives, and at worst it is about the creation and weaponization of opposite facts.

They say that Climate Change is real. We say that it isn’t.

They say that COVID is real. We say that it isn’t.

They say that 20 children were gunned down at Sandy Hook. We say that it didn’t happen.

Action, reaction.

It doesn’t matter how little face validity there is to the story. It doesn’t matter that the parents hurt. All that matters is opposition. In this view, information doesn’t have to have the quality attribute of truth for it to be useful.

Ideas move people. We’re kind of hardcore about that idea in the West. There is certainly a sense that so many systems are failing to the point that there is no trust. And some people are taking the lack of responsiveness in very unproductive directions. Violence is stupid action.

In this way, Alex Jones and his virtual goods about Sandy Hook are a reaction to what an identifiable audience wants. The advertising is baked directly into the information itself. Alex Jones placed advertisements for his products directly into the trial itself. The vertical integration is total. There is an audience that demands the virtual good that Alex Jones sells. There is an audience for the product the rage mongers produce. In that set of perceptions, the information they aggregate is timely, relevant, and intelligent. Truth is optional.

A Way Forward / Is There A Way To Rebuild Trust?

The decision to extend trust rests with the individual, not the institution. The risk in trusting somebody rests with the giver of trust. The choice to pay attention rests with the individual. They either tune in, click, or load — or they don’t. They either sell their attention to an institution, or they don’t. A lot of people made the choice to pay attention to things besides the news. Audiences for mainstream outlets have been declining and will continue to decline unless audiences choose to extend trust once more.

What’s the incentive to take the risk? What is changing? Is there a willingness, at all, on the part of mainstream journalism to change?

In one way, the questions sound absurd. It’s a bit like asking if the horse and buggy industry will change in response to the horseless carriage. The answer then was no. Tens of millions of horses became meat and their industry became a specialized one rooted on sports betting and status goods. Likewise, tens of thousands of journalists were rendered into other professions. Billionaires buy newspapers like they buy ponies. This isn’t new. All English-language newspapers in New Brunswick have been owned by a single billionaire family for decades. It all reinforces the idea that outlets don’t exist to serve the public.

I have difficulty imagining any existing institution earning the opportunity to win back half of the distrustful population. For one, the very forces causing the accumulation of distrust likely don’t believe they’re causing it. For two, even if there was acceptance of accountability, how could they change? What would they change into? Decay requires only a commitment to the status quo. Transformation requires a commitment to change in response to learning.

I have an even greater trouble imagining, if reform were to happen, a market conversion rate exceeding 25% over the course of twenty years. In part, the pace of technological diffusion for products the public wants to buy has been accelerating, but, it still takes quite a long time. That’s for products that the public wants. It seems unlikely that people are willing to sell their trust again to the same set of actors. The industry will have to boil the bones and the shoes for what little sustenance is left.

Stasis. Decline. Decay.

Is the dominant model conducive to rebuilding trust?

The dominant model is that you can pay an increasing number of contractors to produce content and then put ads alongside it, and then, buy a goat from a local farm, go in front of Meta and Google headquarters, and sacrifice it. You take your chances when the distribution of information is centralized into newsfeeds. The US government antitrust investigations have uncovered a number of backroom deals. The rot may be gilded and deep. The ecosystem in which Meta, Apple, and Google are the apex predators doesn’t seem like it’s working out for Buzzfeed, is it?

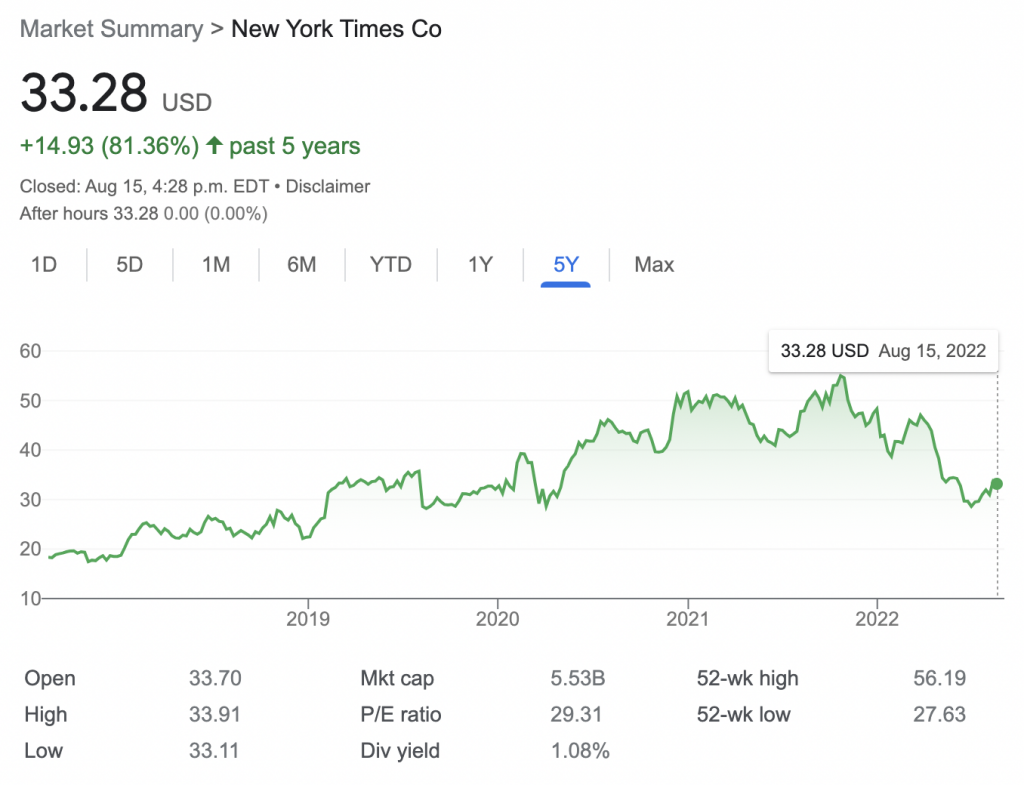

The Management Science on the subscription model is in [2]. It was a painful decade, but Aral and Dhillon got in there and got the real data. The NYT’s subscription strategy was successful in that they’ve survived. It’s a little bit sideways. But there it is.

That offers a clue to the future.

Subscription models create a direct channel to an audience, and create a lock-in dynamic between what the audience values and what the virtual good producer creates.

What comes next?

The central axiom of liberal market economics is pretty clear: if you want it, demand it. The best way to get the truth is to demand it. Vote with your wallet.

For an operation to be capable of delivering the truth, it needs at least two things: autonomy and a margin. It doesn’t need infinite compound growth, but to be sustainable, there needs to be some margin for experimentation, exploration, and drought. It has to retain its relevance to its audience and it must be able to serve it with truth.

It is likely that whatever new decentralized technology enables, there will be some form of a direct support model between the creator and the audience whereby the creator keeps a much larger margin than it currently receives. Hopefully the security offered by decentralized technologies will enable greater innovation outside the centralized technology.

Won’t somebody think of the public? Who will coordinate society’s perspectives?

There may be a belief amongst some journalists and editors that they set the agendas for their respective societies. This is an area of vigorous debate, and in the case of a vast swath of the population, protest. By virtue of directing our attention to specific framings of specific information, and packaging them as stories, they help tell the public what to think and how to think. There may be a story that major news outlets were referees, but this is not true. Most journalists are anti-corruption types. So, they’re fundamentally players. And valuable ones. They’re important for disinfecting our institutions.

The trend is towards the of shattering perspectives and mass fragmentation of belief. The 20% of society that chooses to remain informed will seek increasingly truthful sources of information and attempt to aggregate perspectives to discern what is more likely to be true and what is not. They’ll consult five or more outlets and will seek primary documentation. They believe that it’s their duty to be informed so they can hold institutions to account. They’ll find their job harder. The 80% of society, that is just trying to get by and just wants their lives to get better will not pay or cannot afford to pay, for truthful information, will continue to get by, and will continue to shatter. The tune-out drives an increasingly volatile public until either there’s a rebound or there are no longer enough common ideas to hold society together and it shatters.

Subscription models address the 20%. Those who work in finance pay for information that is timely, relevant, intelligible and truthful. Many in the 20% pay for news. Independent subscription creators are not mass medias. They don’t coordinate the perspectives an increasingly shattered, and suspicious, 80%.

I want to believe that people eventually get tired of being misled and that trust ultimately has a lower bound limit. I have no evidence to back that belief. It’s just optimism that systems in modern democracies are slow to respond but unstoppable once they get moving in a direction.

The quality attributes of virtual information goods matter. Wouldn’t it be fantastic if more than one institution could sustainably retain the independence and autonomy necessary to tell the truth while serving their audience with intelligibility, relevance and timeliness?

[1] This post is an effort to contemporaneously document some of the forces we experienced in the aftermath of COVID and at the beginning, middle, or end of the conflicts that are rippling through Canadian-American society.

[2] Aral, S., & Dhillon, P. S. (2021). Digital paywall design: Implications for content demand and subscriptions. Management Science, 67(4), 2381-2402.