How Social Entrepreneurs Search

This story begins in a lecture room on an upper floor at Temple University in Philly on a pleasant summer day in 2018. John Hauser is delivering a cracking talk on recommendation engines. He launches into an aside about how the best real estate agents on earth facilitate their consumers’ own discovery of their own preferences. He’s challenging conventional doctrine. The grizzled grizzlies fold their arms and lean back in their chairs. The students from KU lean forward. I catch Luo’s eye and exchange smiles. We’re beaming. I got my popcorn ready. This is gonna be good.

He tells a story about how an excellent real estate agent will listen patiently as you state preferences, and then they go onto to show you three very different homes, with very different features, in an effort to get the consumer to understand their own preferences as they experience their preferences. And he relates this back to earlier work in the eighties tracking the financial performance of real estate agents to their search facilitation capabilities. This kind of argument, about how preferences update, means more complexity and likely, probably, threatens several established lineages.

The presentation, and the ideas we exchanged afterwards mattered a lot to me. Dzyabura and Hauser published their findings in 2019 and it’s well worth a read – it’s all there in terms of the state of the art of what Marketing Science knew of RecSys at the time – banditry, Weitzman and all the hooks into the consumer choice lit. I looked for the agent performance reference from the eighties, didn’t find it, but they refer to Rogers (2013), which is useful.

My mind about learning changed that day. Before I was a bit less flexible in adjusting my beliefs. These days, I hold my beliefs about preferences a little bit less tightly. It’s a bit of a shift from doctrine to policy. Doctrines you hold tightly. Policies you use as tools. I talk to my real estate agent differently. I still provide a list of postal codes and parameters, but I’m quite a bit more open to divergence and learning about the consequences of my own imagined preferences. Updating matters a lot.

It changed my mind about the art and science of giving feedback in the design process. I didn’t get anything approaching formal training in giving feedback until well into 2011, and even then, it was geared more towards to creativity-amplification, initiative-preservation, and ego-personality-management. There’s something that is happening inside my own mind as I experience the results of my own preference expression. I’ve come to love ChatGPT and Midjourney so much because of that relationship.

It is too easy to fall into the trap of questioning why people don’t already know their own preferences. Most people don’t know they don’t know what they want, and often don’t have tools to figure it out on their own. It’s why creative agents know how to be creating about showing.

That insight changed the way that I engaged strategy.

What if we shopped for visions in the same way we shopped for a house? What if managerial decision making and consumer decision making had everything in common? What then?

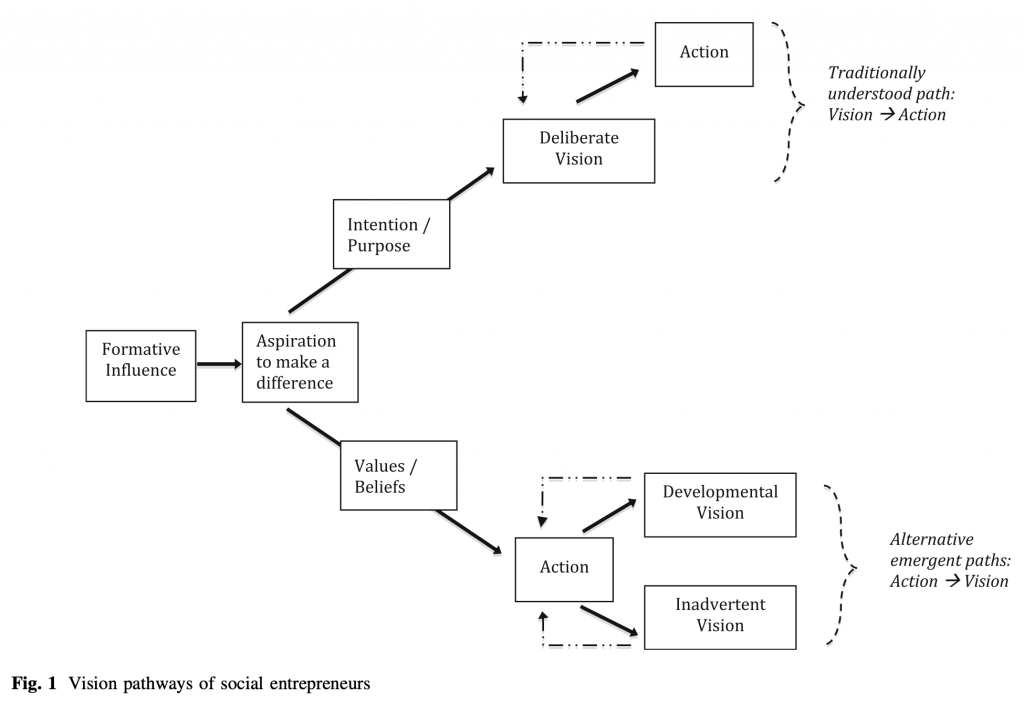

Waddock and Steckler (2016) describe two pathways for how social entrepreneurs search for a vision.

The traditionally understood vision-to-action pathway starts with a formative influence and an aspiration to make a difference. That aspiration informs an intention or a purpose, which in turn creates a deliberate vision, which spurs the action.

In the alternative, emergent paths, Waddock and Steckler suggest that formative influences and aspiration are still at the root, and that values and beliefs drive action, and then, during that action, a vision either develops, or, emerges inadvertently.

Okay so what?

I’m holding onto a belief that deliberate visions are more prone to lock-in than the emergent path. They’re more likely to become doctrine. I worry about hard lock-in quite a bit because if the entrepreneur is successful, their fingerprints (sadly) become the labyrinth that people, decades later, will wander through. It doesn’t seem that people are great at estimating how long their decisions will endure (Thelen, 2004). Understanding the distinction between what is likely to be reversible decision, and is not, is a key input in accurately estimating and using the flexibility reserve of an organization.

There’s nothing wrong with having a strong vision of the future and working towards it. In aggregate, we all benefit when so many entrepreneurs, both social and profiters, point at the sky and give it all. Some of them break through and achieve great things.

I wonder about retaining flexibility while you learn about both your own preferences, and what the world needs. The consumer behaviour literature is filled with the dissonance between what people say they want and what they do. Learning the potential for action in that gap is valuable, and perhaps, leads to a better sequence of decisions add up. Some readers recognize this as the concept of gradient-descent, others as the rate of learning, or the OODA loop rate. If incrementalist discovery is stepped evenly, or uses diminishing sized steps, then that could be a recipe for mediocrity. Decelerating incrementalism is a pretty terrible word because not only does it have a bad mouth feel, but what it represents is pretty terrible. Resistance to updating accumulates and is inertia.

What could be more terrifying is that the difference between success and failure could dependd on the shape of reality in relation to the arbitrary point of where you began your journey! One person’s descent into mediocrity and another’s march around it and onto success could be random.

Maybe that horror informs the heuristic that maybe if you’re feeling too much optimization, then it’s time to open yourself up for bigger steps? Maybe it’s time to start pulling that exploration bandit a lot more often? Maybe it leads to breakthrough?

John Hauser’s intuition about how people experience their preferences, and how agents facilitate those experiences, is useful. It changed my mind about changing my mind.

It could change yours too.

Sources

Dzyabura, Daria and John R. Hauser (2019). Recommending Products When Consumers Learn Their Preference Weights. Marketing Science 38, 3 (May 2019): 365-541

Rogers A (2013) After you read the listings, your agent reads you. New York Times March 26, 2013: F4.

Thelen, K. (2004). How institutions evolve: The political economy of skills in Germany, Britain, the United States, and Japan. Cambridge University Press.

Waddock, S., & Steckler, E. (2016). Visionaries and wayfinders: Deliberate and emergent pathways to vision in social entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Ethics, 133, 719-734.