On Analytical Business Question Spaces

Begin with five statements:

1. The set of business questions that could be asked is infinite.

2. The subset of business questions that could be answered by our current toolset set is very large, but ultimately finite.

3. The subset of business questions that, when answered, could be valuable, is a smaller, finite set.

4. This subset is volatile.

5. The current analytical paradigm is ill equipped to grapple with statements 1 through 4.

Unpack these statements:

1. The set of business questions that could be asked is infinite.

Consider every single combination of characters and numbers that can be packed into quotation marks, ended with a question mark. Consider writing all of these down. You’d end up with millions of slips of paper with questions like:

“jdajfkdjak jdkjla dkeieuo kalkdjj?”

And

“Who are the most valuable customers”

And

“What caused customers who purchased the Samuel Jackson Snakes on a Plane commemorative plate who also happened to visit the discount page on the Snakes on a Plane microsite to convert?”

And

“What were married mothers, living in Colorado, with two children under 5 and four children from another marriage older than 12, who twitter, do between the hours of 2pm EST and 3pm EST on the Second Tuesday of every month ending in ‘Y’, for the past four years, accurate to within +/- 4%, 19/20?”

Everybody who reads this blog should have been asked questions like those above at one point or another in their career. There are certain questions that make you wince and ask “why the hell would you want to know that?”

The point remains that the set of questions that could be asked, that are human readable, is infinite. I’d go so far as to argue that it’s the size of the Library of Smith, but I lack that skillset that allows me to write elegant proofs in the manner that people who write elegant proofs expect to see them. But I’m not going to withdraw the assertion. If you can find a counter-example, I’ll accept it.

2. The subset of business questions that could be answered by our current toolset set is very large, but ultimately finite.

“jdajfkdjak jdkjla dkeieuo kalkdjj?”

– Don’t know what you’re asking.

“Who are the most valuable customers”

-That would require access to the customer database and a Novo Segmentation. If you have both the access and the tool (a spreadsheet for n<65000) style="font-weight: bold;">3. The subset of business questions that, when answered, could be valuable, is a smaller, finite set.

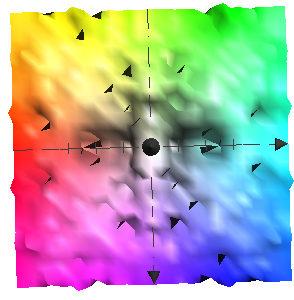

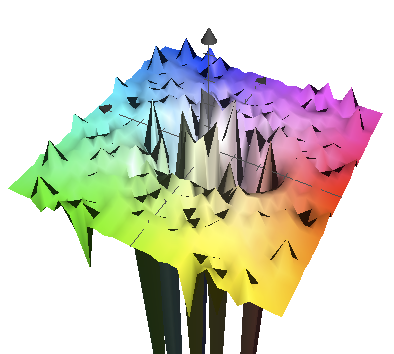

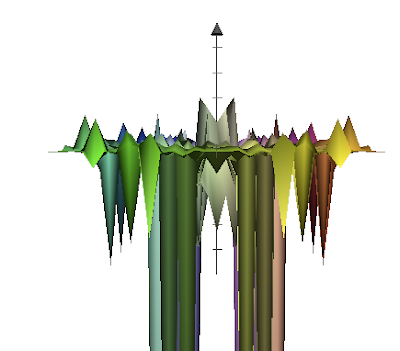

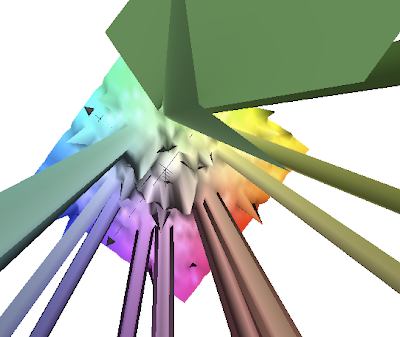

If I were to plot all of these question on a plane – on a surface, with the X-axis being some arbitrary descriptor of the questions, and the Y-axis being another arbitrary descriptor, and plot the potential business value minus the business cost of knowing the answer to that question for a given company n, this is what I’m expecting to see:

There are a whole bunch of questions that, if you keep on throwing resources at trying to answer them, you’re not not going to derive any business value at all from them. They’re like black holes. Only that they’re not actually a hole in the plane. But they might as well be.

There are a few questions that, when answered efficiently, will yield very nice returns.

There are other questions that are more or less flat. There’s still lump in there, just at much smaller scale.

Novo has pointed out that good marketers know the 12 to 15 questions that yield the highest returns for businesses: and I agree. I’ll point out that an experienced marketer will be able to evaluate the subset of millions questions and say, “wtf, that has no value”.

4. This subset is volatile.

Knowing the most valuable customers for sheet music in 1922 was far more valuable than it was in 2006.

Factor in that business conditions change, economies change, CMO’s and CEO’s churn.

The question surface is volatile.

5. The current analytical paradigm is ill equipped to grapple with statements 1 through 4.

A paradigm is a way of looking at the world that is loaded with bias, definitions, jargon, tools, methods and prejudices.

The present analytical paradigm is heavily based around tools – the most common question you get these days is “You know

The problem is that the paradigm is product centric. It’s not business question centric. It denies that there is there is a surface outside what is offered, and worse, denies that the set of business questions shifts over time.

And analysts ourselves are part of the problem.

Instead of asking “what is the subset of questions we need answered” up front, we’re jumping to what CAN be answered by a single tool versus another tool. Worse, certain analysts are receiving what essentially adds up to payola by aligning with specific vendor technologies. The more complex and technically difficult the product: so much the better.

And there it is.

What say you? Are you part of the solution or part of the problem?

What does the Philosoraptor think?

3 thoughts on “On Analytical Business Question Spaces”

Christopher, it would be so interesting to crack your head open and figure out how that brain of yours comes up with these posts. I will attempt a response in your vain.

Indeed, the paradigm is product centric, not business question centric.

To turn a phrase, “What can be Measured is not always worth Managing.”

Web analytics is full of such measurements, especially surrounding new technologies, where (in reality) what is worth measuring is usually the same damn things that are always worth measuring.

Ultimately, there is only 1 question you need the answer to, and this is how to answer it:

1. Take a random sample of a population

2. Do something to treat the rest of the population

3. Compare the effect of this something on the treated population to the random sample not receiving the treatment

4. Measure incremental profit on the treated population

5. If there are incremental profits (net of all costs), the treatment is worth doing. If not, the treatment is not worth doing

It’s really that easy. Every time, for every program, the same thing.

Any measurement other than this one is superfluous and in truth, is simply Measurement for the sake of Measurement and not Management.

Or, it’s laziness.

Or, it’s tool infatuation.

Good points.

We haven’t fully realized yet that IIS/Apache log formats put us in a conceptual box (shall we say paradigm?) back 15 years ago.

@jimnovo

There’s power in those simple 5 steps. That’s the very essence of the scientific method.

I think the scientific method is the best way to deal with the volatility surface.

We don’t yet have discipline in deciding which questions to ask – even amongst ourselves. And I’m probably just old enough to realize that such discipline will elude us for a very long time.

Your point is well taken though: I should chill out and operate the algorithm.

@JacquesWarren

We’re all prisoners of our time.

Comments are closed.