The Product Vision

“I’m seeing things

Believe me

I’ve never seen before

Little things

Deceive me”

Seeing Things, Theme Song, 1981

One common formula for a product vision comes from Steve Blank (2010, 2020). It goes like this: “For <customer segment> our product, <product name> is a <name the sector that customers say> that <benefit>. Unlike <competitors>, our product <discriminator>. Our product is <product name>.”

And each bit of that formula can be systematically turned into a set of hypotheses that can be tested and refined until the vision is sufficiently true, or likely, to create a wonderful business if scaled.

Blank himself repeats that entrepreneurs are rule breakers, so it’s really up to them which ones they want to break. Osterwalder and Pigneur’s (2010) business model canvas is associated with this format. There are useful tools for making connections amongst business models – like Gassmann et al’s St. Gallen business model navigator (2013), and offer some fibre for exploring other kinds of business models (Assadi, 2021).

Master’s and Thiel (2014) emphasize that an entrepreneur needs to have a heretical idea. Mollick (2020) cautions that idea has to strike a balance between being differentiated enough to be unique, but legitimate enough to be fundable – what Johnson (2011) would call the adjacent possible.

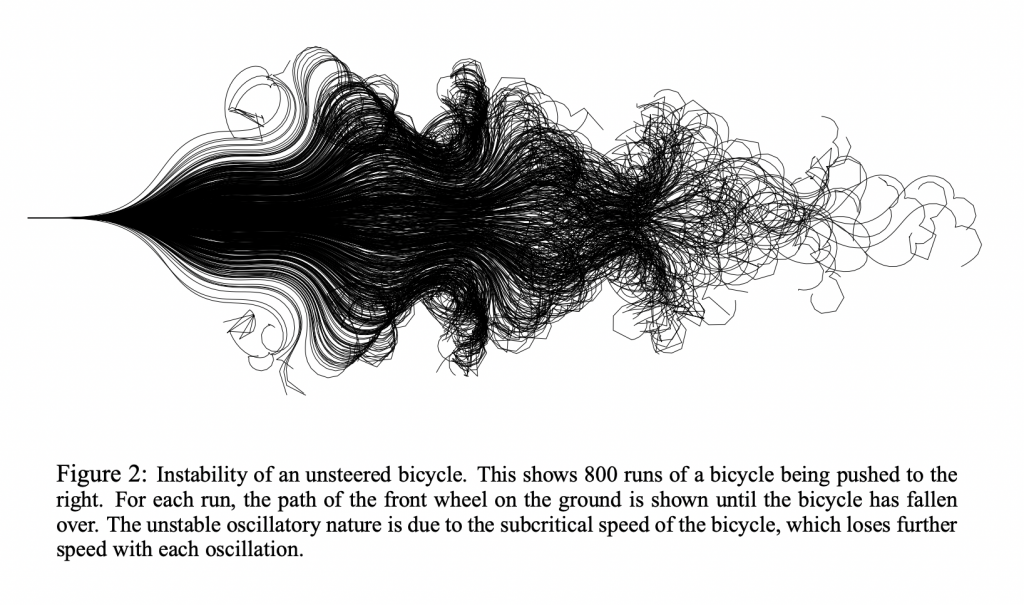

Imagine the adjacent possible as a space. To the left of a dot is everything that has happened before the present. To the right, everything that can occur into the future. One of the simplest ways to visualize this is to repeat a meme from Cook (2004) about bicycles. See below:

Look at all the possibilities created by a bike getting pushed. Look at linear so many of the paths are before the bike death spirals! Some things in the future are more likely than others. Some of those reasons have to do with Thelen hard lock-in (2004) and some of those reasons just have to do with where and how the future is likely to be distributed. Sometimes I wonder about the structure of the knowledge tree and the distribution of the adjacent possible. To explain a bit more about this I’ll repeat another common meme.

A common meme in pop literature is Gutenberg living in a wine region. People in this area still used an ancient Roman technology to press grapes using…a press and a screw. A grape press is an adjacent technology to a printing press. Kind of obvious in hindsight. Not so obvious then. There was a lot more to it than that. Moveable type and ink were two additional technologies that Gutenberg brought together. I wonder if more formalized explorations into the effects of applying heat to different kinds of rocks during that era also enabled Gutenberg? It’s all in the combinatorics of ideas and execution that pulls the future possibilities into the present. What’s possible today that wasn’t possible yesterday?

Given that humanity, as a collective, knows so much, and comparatively shares so little (!), how many potential connections are there today that have yet to be made? Like an unsteered bike, the path through the structure of the adjacent possible may be more inevitable than others.

Take, for instance, the idea for YouTube in 1993. 1993 was too soon for YouTube. The Internet was text only because bandwidth was extremely expensive. The infrastructure wasn’t ready for it. About about the idea for YouTube in 1997? Still too soon. 2005? Broadband technology was just on the edge of tipping 50% penetration in 2006. There was just enough technology, and the future was just spread good enough for the idea of YouTube to take off. There’s an entire industry that’s about predicting the adjacent possible, and a specialization of that industry for explaining it to managers (See: Kaivo-oja, J., Lauraeus, T., & Knudsen, M. S. (2020)).

This is in part why statements like “My uncle had the idea for Uber in 1991” induce eye rolls. Cool story! Timing matters.

In general, the problem in bringing a vision forward with new technology is the timing issue: Why now? There are some combinations of society and technology that are ready now. And there are some combinations that are not. There may be far more path dependence that is more obvious in hindsight than it is in foresight.

Streams

I encountered Kingdon and Stano’s (1984) Agendas, alternatives and public policies twenty years after it was written. Kingdon described the process of how people, energy, problems and solution came to enter the can. The core allusion that Kingdon brought forward that what you had different streams of activity, and when those streams crossed, they created policy windows. I thought of these streams like in Ghostbusters. Letting the streams cross would unleash a lot of energy and who knows what would happen.

Different streams had different waves to them. The routine of budgeting for the next fiscal year was an example of such a cycle of problems and solutions coming together regularly at specific times. Kingdon called these routine policy windows. Another was the budget surplus which is a somewhat irregular policy window. Sometimes a budget surplus is a problem looking for a solution. Sometimes it is a solution looking for a problem.

I read it after Cohen, March and Olsen’s Garbage Can Model (1972) had already left quite an impression. They described streams coming into a Garbage can and the the math of what happened inside a decision process. Kingdon focused on the nature of the streams themselves.

I walked away from that, and subsequent reading on how institutions learned, thinking that whenever streams of participants, high energy, problems, and solutions collided, they’d be capable of forming a new Garbage Can – a new organized anarchy. This is how I thought of institutions like the EPA, NRCAN, and Environment Canada coming into being. A much nicer term for lower energy processes within institutions is to call them whirlpools from Howlett, M., McConnell, A., & Perl, A. (2015).

Later, I made the association to stream, institutions, and startups.

Multiple startups are born when a stream of problems, a stream of solutions, a stream of participants, and a stream of energy collide. It was only relatively recently, in 2019, that I wrote about the idea that power and capital were roughly equivalent. If you apply enough power, with enough purpose, you can will many things into existence. You might even be able to bend the adjacent possible just a bit closer.

Imagine, taking you’d take all the problems and line them up, and all the solutions and line them up. Then let time move forward. How do you imagine those streams of problems and solutions would weave? Do they weave in a flat 2-D space? Or is there a third, fourth, and maybe even a fifth dimension where they might only glance each other?

Consider NFT’s, or Non-Fungible Tokens. For one stream of high energy participants, the NFT is a solution to a problem. For another stream of participants, it’s a problem looking for a solution. And for many observers who can’t look away it’s the very definition of a Garbage Can. A reasonable person can examine the technology on its own merits and consider all the problems a given technology may enable. It’s always interesting to think about why streams entangle themselves. Why is that that particular group of people are binding themselves, weaving themselves, around that particular problem or that particular solution? Why are they doing that?

Many people would just look for trends and apply a pretty basic structure to generate visions. Identify seven or nine trends in a table and iteratively weave them together, and then simply ask the same questions over and over again. What does the <problem> mean for <solution>? What does <participants> mean for <problem>? How will <energy> change <solution>? There are at least 16 different combination in the table, against a basic combination matrix – well, you got yourself a space that can be explored for a very long time. To render this concrete – what does privacy mean for the metaverse? What does NFT mean for artisanal bread bakers? What does the great resignation mean for quantum computing? How will impact investors change the meaning of virtual reality forever? How will Taylor Swift change artisanal bread NFT’s forever?

While solutions seem to attract the most passion, problem streams seem to attract the most energy.

Given the sheer size of the possibility space, not every question can be answered, or even, should be asked? Some games simply aren’t worth the effort of playing. Not every question needs to be written, and, I’d argue that given the size of the opportunity space, is even written.

Like in Ghostbusters, when streams cross, they create heat and light. Sometimes streams really do entangle and last for a long time. The weaving of a problem, solution, energy and participants came together to create millions of Open Source Software (OSS) projects, with some Garbage Cans truly living up to their name and reputation, and most withering into nothing. Or like anything else that’s creating heat and light.

There was something…unsatisfying about Kingdon’s random policy windows. That, was it really truly random, or were there causes in the deeper structure of why streams converge when they do? Do streams themselves emit energy that makes some collisions more inevitable?

People who write such questions and expend energy in validation are important to the search. We can learn a lot from watching all the efforts.

The act of validating is interesting and extremely useful, in the aggregate, because it’s a form of exploration and search. It can add information to the entire body of knowledge. It can help us all understand the map of the adjacent possible. What’s now. What’s soon. What’s too soon.

Information about streams is very valuable because it helps us understand so much more.

Suppose you have a product vision? What now?

What’s great about liberal democracies is that we get to try to expand the adjacent possible. So try. You get to choose.

Validating Product Visions

The same gifts that enable you to create a product vision can be blockers that prevent you from realizing any product vision.

Blank emphasizes the link between customer and problem. It’s not enough for you to see that a customer has a problem. The customer has to be aware that they have a problem. And then, the customer has to be able to do something about it. Willingness To Pay isn’t enough. They have to have the Ability To Pay. This idea was repeated by Thiel and Masters (2014) with the optimism that if one customer existed, then the potential for n customers existed.

And this feels all linear and straightforward. Start with a need. Develop the vision, then the customers, then develop the product, then, if there is a business at the other end, scale the business. In that order. It seems straightforward.

There is a problem though in how some customers might not be indicative of future customers. There is considerable heterogeneity in the preferences among multiple customer segments. There’s cause for optimism. And there’s cause for caution.

The core issue that I have with Thiel and Masters with that optimism is the existence of harbinger customers Anderson et al (2015). These are people who are associated with failed products. Think Crystal Pepsi, or, as one speaker at an ISMS Conference put it: “Think about the people who really like the Xune over the iPod.” Simester, Tucker, and Yang (2019) went onto group harbinger customers into zip codes. What’s fun about the entire concept is that would seem that harbinger customers seem to cluster. It take a very special kind of mind to deduce why this is the case.

This is to say, even practicing orthodox Blank-Thiel customer development is no guarantee that you will validate a product vision against a market that will lead to creating a wonderful business. It leads to a wonderful kind of thought experiment. Suppose you become aware that you’re acquiring harbinger customers? What do you do?

Which is easier: changing the customers of a product or changing the product for the customer?

The orthodox database marketing answer is that customers are destiny and they’re far more locked in. The orthodox technical management answer is that technical decisions generate far more lock in. The decision to pivot could be informed by how many customers have been accumulated and how much technical debt has been accumulated. If the sunk cost mental bias can be suspended, the startup retains quite a bit of flexibility. If the participants in the startup can’t get through their own mental bias, then they’ve locked themselves in.

For example, suppose a startup has 50 paying customers representing 100 units of recurring revenue over the next 12 months (factoring in churn), 200 units of technical debt, and 500 units of capital. They’re learning that most of their paying customers are harbingers. Do they use their 500 units of capital to pivot the business and discover another set of paying customers, inevitably accelerating the churn rate as they do it? Or are they effectively locked into their 200 units of technical debt and 50 paying customers? Sound familiar? Moore (1992) describes just such a choice in Crossing The Chasm between Early Adopters and the Early Majority. (I make no claim that all Early Adopters are harbingers at all – I’m just recalling the similarity in the choices).

In another example, suppose a startup has 50 paying customers representing 1000 units of recurring revenue over the next 12 months (factoring in churn), 500 units of technical debt and 100 units of capital. They’ve learned that their customers are harbingers. Do they use their 100 units of capital to pivot the business and discover another set of paying customers, inevitably accelerating the churn rate as they do it? It seems quite a bit harder, doesn’t it? Do they seem locked in? Sound familiar?

The linkage between customer development and product development is sticky. Not all the choices are as easily reversible as they might seem from the outset. Some choices are sticker than others.

For instance, the choice of customer to focus on seems to eliminate large swaths of customer segments from the outset. The choice to sell audiences to advertisers effectively eliminates entire parts of the population and massively constrains what can be built (I recently wrote about this effect with respect to content, the effect very much persists within the technical side of the product as well). Regardless of what an entrepreneur says or might even have fooled themselves into thinking, those who pay have sway. The choice to sell a software directly to a customer in exchange for money effectively eliminates huge swaths of customer segments from consideration. Over a billion people remain unbanked. They don’t have an ability to pay money. They pay with their attention.

Enterprises are composed of a large number of people who are constrained in their ability to create new value by rules that are designed to, at best, manage risk, or at worst, eliminate it altogether. Small and Medium sized Businesses are composed of a smaller number of people who are constrained in their ability to create new value either by their size, or, by the rules that may or may not been consciously designed to manage risk. A pivot from Enterprise to SMB might sound trivial. It might be easier for some organizations than others.

Taking it the other way, the choice of product to focus seems to eliminate large swaths of customer segments from the outset as well. Focusing on a mobile phone app leads back to the advertiser-as-a-customer versus customer-as-a-customer choice. The choice to build a console game, a PC/Mac game, a card game, or a board game all similarly narrows the space.

Business models matter.

The choice to start down one path may generate more lock-in the further down you explore. Some are stickier than others. I’m not sure why this must be so. But they are so.

This applies during the product development process.

The cost of change during the scaling phase is high.

The gift of having a product vision is wonderful. It gives you a starting point to push that bike. The validation of a product vision can generate lock in, which may or may not be a great thing. It can be extremely hard to tell.

To Accumulate Knowledge As You Explore

The bulk of the academic literature encourages entrepreneurs to accumulate experience, search, and explore. The bulk of the pop literature encourages entrepreneurs to emulate stories that are misremembered at best or are convenient stories at worst. Most successful entrepreneurs never talk publicly about all the paths they explored before finding the right one. I’m not sure why they don’t. It’s really about search.

A Product Vision gives you the gift of a place to start your inquiry and the journey to struggle against mental bias itself. If you envision your product being used by college students looking to pass their exams honestly, without cheating, then start by asking college students short questions and listening to them. If honest people are harbinger customers (what a world!) then you get that knowledge.

The adjacent possible is a huge space. I don’t think it’s every been as large today, for so many in the West, then it has ever been. It’s massive. Combine streams and see what happens.

So it makes a lot of sense to accumulate as much knowledge as you can while you explore the edge.

Sources

Anderson, Eric, Song Lin, Duncan Simester, and Catherine Tucker (2015), “Harbingers of

Failure,” Journal of Marketing Research, 52(5), 580-592.

Assadi, D. (2021). What is a P2P business model?. In Encyclopedia of Organizational Knowledge, Administration, and Technology (pp. 758-774). IGI Global.

Blank, S. (2020). The four steps to the epiphany: successful strategies for products that win. John Wiley & Sons.

Cohen, M. D., March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (1972). A garbage can model of organizational choice. Administrative science quarterly, 1-25.

Cook, M. (2004). It takes two neurons to ride a bicycle. Demonstration at NIPS, 4.

Gassmann, O., Frankenberger, K., & Csik, M. (2013). The St. Gallen business model navigator.

Howlett, M., McConnell, A., & Perl, A. (2015). Streams and stages: Reconciling Kingdon and policy process theory. European Journal of Political Research, 54(3), 419-434.

Johnson, S. (2011). Where good ideas come from: The natural history of innovation. Penguin.

Kaivo-oja, J., Lauraeus, T., & Knudsen, M. S. (2020). Picking the ICT technology winners-longitudinal analysis of 21st century technologies based on the Gartner hype cycle 2008-2017: trends, tendencies, and weak signals. International Journal of Web Engineering and Technology, 15(3), 216-264.

Kingdon, J. W., & Stano, E. (1984). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies (Vol. 45, pp. 165-169). Boston: Little, Brown.

Masters, B., & Thiel, P. (2014). Zero to one: notes on start ups, or how to build the future. Random House.

Mollick, E. (2020). The Unicorn’s Shadow: Combating the Dangerous Myths that Hold Back Startups, Founders, and Investors. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Moore, G. A., & McKenna, R. (1992). Crossing the chasm.

Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business model generation: a handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers (Vol. 1). John Wiley & Sons.

Simester, D. I., Tucker, C. E., & Yang, C. (2019). The surprising breadth of harbingers of failure. Journal of Marketing Research, 56(6), 1034-1049.

Thelen, K. (2004). How institutions evolve.

Thiel, P. A., & Masters, B. (2014). Zero to one: Notes on startups, or how to build the future. Currency.