Will Covid-19 change population density?

Canadians are a people shaped by physical and social geography. Both explain a portion of why we are who we are, and how we relate to each other.

Covid-19, an executable snippet of code wrapped in protein with the sole goal of persistence, is shaping us. It has already affected our social demography. Will it change Canada’s social geography?

What It Is

Population density is a pretty good indicator of attitude. I can’t make the claim that it’s always causal for all people, After all, did living with 25,000 others in a square kilometre in downtown Toronto make you more conscious of mental health challenges facing the population, or were you always conscious and chose to live with others who are conscious of mental health challenges facing the population? Did living with just one other person in a square kilometre make you more aware of the threat of wildlife to your own life and limb, and shape your attitude towards long guns, or, did you move out to be with nature because, in part, you liked wildlife and long guns?

Four generations of Canadian policymakers certainly believed that population density was deeply causal. The resistance to population density got its roots around 1905, when density was blamed for outbreaks of Bolshevism. For the next 75 years, politicians at every level fought the underlining transportation economics and market incentives for density to occur [1]. Could they have been wrong for so long? [4]

Ground truth is likely somewhere in between. We shape our environments and our environments shape us.

What’s Changing

Depending on where you draw the lines around systems, Covid-19 is either an endogenous shock or an exogenous shock. Regardless of where your stance on globalization and the resiliency of global economic systems, it was a shock.

It has given many people the incentive to physically stay away from each other. The strength of that incentive is moderated by own personal assessment of the risk. And we all have different ways of acquiring information about risk, processing risk, and managing risk.

Both the shock, and how individuals are changing how they manage risk, is changing.

I’ve been reading predictions that people aren’t going to want to take public transit anymore, driving a demand for single occupant vehicle usage and bicycle lanes. And that living in high density communities isn’t going to be popular.

I remain open to be convinced.

Why It Matters

Unlike policymakers of yesteryear, I associate density with specialization, and further, I associate specialization with economic prosperity.

I resist the use of the word cause. Density without security is density without opportunity. There can be no economic prosperity without security. There’s a certain amount of social infrastructure, in particular around justice, fairness, hygiene and services, that has to be in place to enable prosperous density.

In order to improve the general state of humanity, knowledge must be wrested from the claws of nature. Nature, by its very nature, resists being known [2]. It takes a lot of brain power to obtain that knowledge, and some more brain power to put it to use. So it follows that in locations where there is a lot of brain power concentrated in a space and on a problem set, a lot more knowledge is going to be obtained. Then, yet more brain power is used to exploit that knowledge for the general advancement of humanity, with different reward functions and timelines. Social proximity seems to amplify imitation and the diffusion of new technology.

Information Technology, starting with verbal language, then symbolic representation, the tablet, the stele, the parchment, the press, mail, pamphlet, newspaper, telegraph, telephone, radio, television, fax, and Internet has made the world progressively smaller. We’re socially closer together even if we’re physically distant.

There was already a remote-work evolution well under way prior to Covid-19. It just got a little bit more pep. It may be entirely possible that specialization can become deeper on the Internet, as a result of remote-work and remote-collaboration. This has been the norm in open source for decades already. There is still much to be desired about the state of social capital in many open source communities [3].

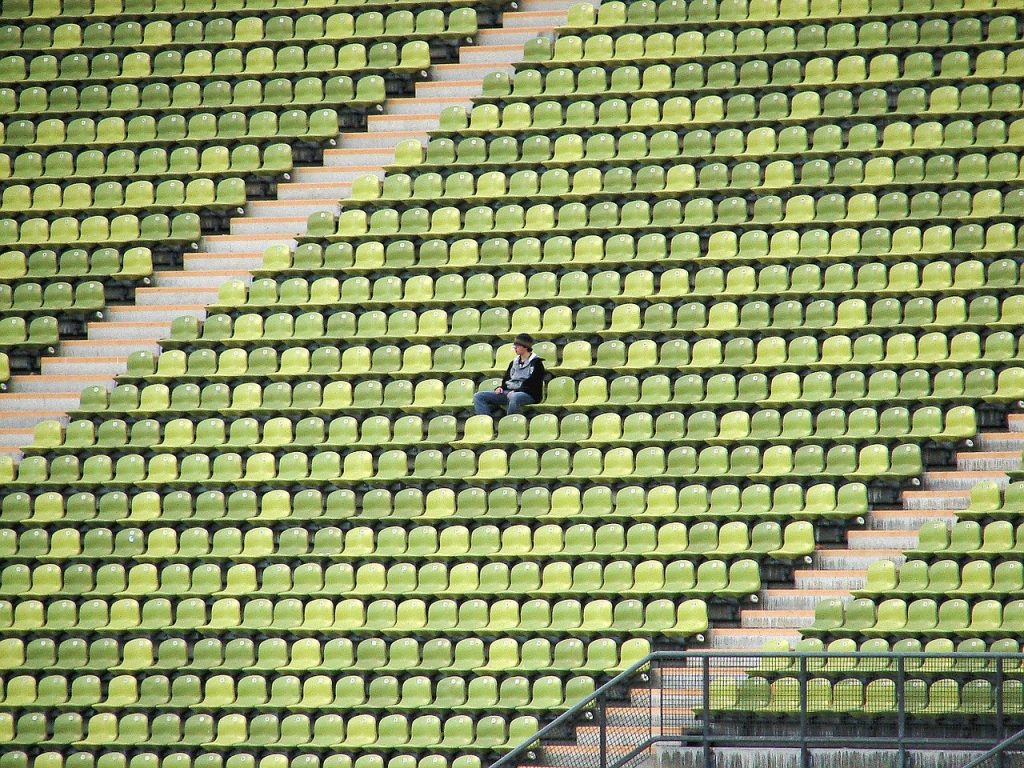

The root of my skepticism about it is based on all the micro and meso interactions on has by being in a physically dense environment. The thing I miss the most about some conferences aren’t so much the presentations – it’s the hallway outside. It’s the couches. It’s the café. It’s the same in Toronto – where a happenstance encounter with a brilliant person at a meetup can kick off a whole set of meetings. Density creates a lot more opportunity.

Moreover, there is good reason to believe that many organizations are heavily reliant on the social capital and connections made by their employees during the offline era. Without new mechanisms to integrate newcomers, which is new knowledge to many, many organizations will burn through this social capital in 18 to 24 months, and may discover a heavily fragmented internal social network that makes the exploitation of new knowledge all the more harder.

That isn’t to say that it isn’t possible to succeed. It’s just that it requires significant learning and adaptation. Such skills appear to be normally distributed in the economy, and this set of challenges may be too much for many. This shock is a business extinction event.

With respect to transit, in the short run, mass public transportation will not move masses. In the long run, however, the simple physics that are imposed on transportation economics will remain stubbornly fixed. An indicator of prosperity is the movement of people and goods. In most cities, the road surfaces are fixed and the efficiency is poor. Unless we’re planning to arrest all prosperity, there will be increased demand for mass transportation. The efficiency of the road system may improve as the time of movement shifts. Those shifts can be driven by remote-work and improved logistical machine intelligence.

The same natural laws apply to residential density. So long as people want more opportunity and more experiences, they will continue to pursue an urbanized life. In the short run, residential density may decline very slightly. In the long run, like moths to a light, people are attracted to better lives.

It’s for these reasons that, while Covid-19 has certainly and temporarily changed our physical density, it is unlikely to permanently change it.

[1] Solomon, Lawrence (2007) Toronto Sprawls: A History. University of Toronto Press.

[2] This declaration should resonate most with the instrumentation engineers first, and statistical practitioners second. The aleatoric mind sure does like to wrestle with the epistemic mind doesn’t it?

[3] For instance: https://hub.packtpub.com/why-guido-van-rossum-quit/ — there are too many other cases to enumerate.

[4] Yes. Yes they were. A form of Canadian socialism-lite emerged on the low density prairies 30 years later.