Product Managing Data Science

In this post, I’ll outline some of the best parts about product managing data science.

Data science is the creation of product from data, requiring a blend of the skills of technology, statistics, and business. Product Management brings and keeps product in the world, requiring a blend of the skills of technology, user experience, and business. All of the challenges of product management appear in data science. And then some.

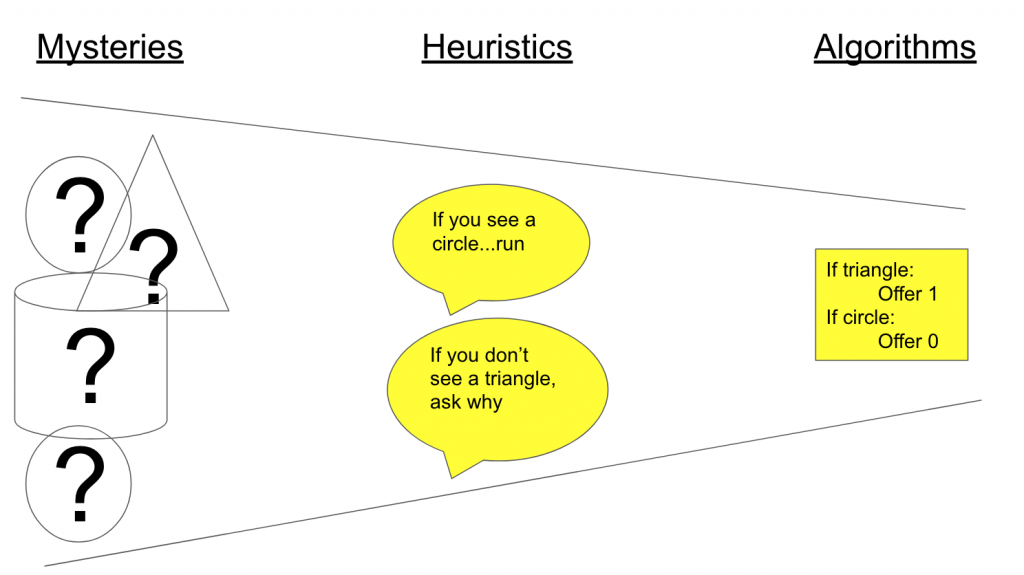

The Knowledge Funnel

The Knowledge Funnel is a concept introduced by Roger Martin in Design of Business: Why Design Thinking is the Next Competitive Advantage (2009).

At the top of the funnel, you got mysteries. It would seem that there are an uncountable number of mysteries. In the middle, you have heuristics, or little rules of thumb. It would seem as though managerial heuristics follow a power law distribution, where there is a small set that are so common to be common sense, and a long tail of novelty. And then at the bottom of the funnel you have algorithms, which are judgement and intelligence that are crystallized to the point that a computer can execute them.

Some managers specialize at the top of the funnel, exploring mysteries and converting them into heuristics. Some managers spend their entire lives in the middle of the the funnel as operators and exploiting heuristics. And some managers uncover hidden knowledge and some of those heuristics into algorithms.

Most product management (and startup) literature focuses on the top of the funnel, most data science literature on the bottom of the funnel. To do product management for data science, one often has to manage the entire knowledge funnel.

Great People. Great Product. Great Profit. In that order. Always. [1] We’ll start with the people.

Helping The Team Through The Knowledge Funnel

A great data science product is built by great people working together in great teams. Any team can be great. It all depends on the conditions.

There is something deeply uncomfortable, disturbing, and exciting about mystery. And that can cause a few reactions.

Some members of the team will want to spend a lot of time in top of the funnel, going so far as to question first principles. Sometimes this is necessary to generate a common enough understanding amongst team members. Sometimes it isn’t.

Some members of the team will want to get straight to sampling data and setting up pipelines. Sometimes this is necessary to generate raw quantitative data to explore. Sometimes it’s too soon.

Some members of the team will want to explore as many managerial heuristics as possible. Some will understand that heuristics tend to underfit the data, and others will trend towards imitating heuristics as closely as possible.

This can be a major source of conflict. Some people want to deliberate and plan through a course of action. Some people want to get things done. Now.

The product manager has a role in managing these reactions into a rough plan that’s deliberate enough to generate sufficient security for some, and enough freedom to explore threads for others. If a team is overly conservative, the product manager can create more exploration. If the team is overly explorative, the product manager can create urgency.

The demand for these skills is especially high in data science teams as the friction is that much more severe.

A data science product team is often multidisciplinary. Different disciplines have different biases in how they approach knowledge generation. Some disciplines tend to be extremely tactical in nature. They can get frustrated with the lack of certainty in the requirements. Some disciplines tend to be very explorative in nature. They can get frustrated by the demand for certainty.

Striking this balance, helping people see each other, and working through the knowledge funnel is among the best part of data science.

Helping The Consumers Through The Knowledge Funnel

Consumers often don’t know their own preferences. They have to learn what they want [2]. I’ve yet to figure out how to communicate this fact in a way that doesn’t alienate. It’s not the case that the consumer is always right, right away. It just takes some time and data to learn about their own preferences and what they really want.

Product Managers encounter an awful lot of static. Customers will often make hard declarations. If the product manager didn’t think about those hard declarations, they become requirements. A laundry list of requirements is no guarantee that it’ll work together. This is in particular why enterprise software was/has been so terrible for so many years – the people doing the buying are often not the people doing the using! Things get mangled. Mashed. Phoenixed.

Product Managers can facilitate the bridge among members of the team and consumers to uncover the mystery of what the problems, solutions, energy, preferences, and jobs that have to be done. Previously I engaged in a little thought experiment and asked what if novels were written like software? Today, I’ll do another one. What if we baked a cake the same way we built data science?

You may have one consumer that insists in email, before there’s even a chance to meet or have a discussion about the problem set, that the cake must be chocolate. They have eaten at some of the best bakeries, and in their experience, the best cakes have chocolate. You may have another consumer that insists that the cake must feature some kind of fruit. And you may have another consumer that has an egg allergy. And a fourth one for good measure that detests chocolate.

The role of the Product Manager isn’t to negotiate with a sample of customers to build some kind of minimax compromise. It isn’t to engage in shuttle diplomacy between consumers, market segments, or waring factions. It may be to create just enough space to ask – what job is the cake hired for?

One consumer may reply that the point of the cake is to be chocolate. Another may reply that they hire the cake to feel full, but feel guilty about breaking their diet, so they’re looking for a lower calorie option. One consumer wants to participate in a social event, but doesn’t want to spend the evening in the toilet. And it’s one consumers birthday and they’d like to share the experience.

Sometimes the consumers discover that they want to share an experience together, but not die, so the product is cup cakes. Sometimes it’s mini cupcakes (Honestly, where does it end with you people?). Sometimes it’s crêpes. Sometimes it’s a semi-edible platform without egg, gluten, nuts, salt, or fat of any kind, that may be filled with a choice of fillings, be it chocolate mouse, foam, glazed fruit, shaved ice, or nitrogen chilled raspberries arranged as a picture of the individual targeted for a birthday ritual.

Sometimes consumers don’t have a lot of cognitive load to get into it with the team. Sometimes consumers do. Sometimes a set of self-referential people start off asking for a cake, and end up wanting crêpes. Product Management can offer just enough safe harbour for the discovery to emerge.

Helping The Investors Through The Knowledge Funnel

Investors have different preferences. They have different reasons for investing their capital. Sometimes the investors are aware of The Knowledge Funnel and enjoy the ride. It’s can be extraordinarily rewarding to both watch new teams discover new things, disrupting sleeping giants all unto itself.

Sometimes investors only care about financial risk and financial reward to the exclusion of all else.

An investor has to work through their own knowledge funnel long before encountering the product team they want to invest in. They often start off thinking they know their own preferences, and they to learn. Many have a set of heuristics that they are enthusiastic to share [3]. Very few have crystallized their knowledge into algorithms.

Some investors have classical business training. Some have not. The Product Manager can assist in their understanding primarily by matching the kind of knowledge that an investor would need to satisfy the specific job they’re trying to achieve. These vary by product lifecycle.

This is a high bar.

Conclusion

Product Managing Data Science takes a lot of different skills: collaboration, facilitation, communication, user experience, design, statistics, business and technology for starters. And it gets a lot more complex from there.

And it’s tremendously rewarding to triangulate the number of perspectives that go into a successful data science product.

It’s a journey.

That’s the best part.

[1] Horowitz (2014) The Hard Thing About Hard Things.

[2] I credit JR Hauser for introducing me to this world and opening my eyes to Weitzman (1979). There’s an entire subfield of Marketing Science that’s dedicated to consumer choice and consumer choice that sits nicely at the intersection of new product development and product diffusion. It’s worth a detour.

[3] Often vigorously. In experiencing over a dozen VC panels at data science oriented conferences over the past decade, I’m mystified by the strength of the certainty expressed in their heuristics. If you have some light to shed on this tendency, I’d love to learn more.